Now Is the Right Time!

As a parent or someone in a parenting role, you play a crucial role in your child’s/teen’s success. There are intentional ways to grow a healthy parent-child relationship. Growing your child’s/teen’s skills to manage anger provides an excellent opportunity.

Children age 11-14 are still in the process of learning about their strong and changing feelings. They do not fully understand the physical and mental takeover that can occur when angry. While striving for more independence, the sense of a lack of control that anger can produce can frighten them, adding to the length and intensity of their upset. It might also humiliate them if they are mad in front of respected others like teachers, siblings, friends, or relatives. Learning how to deal with anger without suppressing it or expressing it by hurting others and themselves is critical. Your support and guidance matter greatly.

Research confirms that when children/teens learn to tolerate, manage, and express their feelings, it simultaneously strengthens their executive functioning skills.1 They can better use self-control, solve problems, and focus their attention. This directly impacts their school success. However, the opposite is also true. Those children/teens who do not learn to manage their feelings through the guidance and support of caring adults may have attention issues and problem-solving difficulties.

Anger is not bad or negative. You should not avoid or shut down the experience of it. There’s a good reason for it. Everyone has experienced someone who has lost control and acted in ways that harmed themselves or others when angry. However, every feeling, including anger, serves a critical purpose. Anger provides essential information about who a person is, what emotional or physical needs are not getting met, and where their boundaries lie. Understanding this often misunderstood feeling is vital to helping your children/teens better understand themselves and learn healthy ways to manage their intense feelings.

Everyone can face challenges with feeling overcome by anger. Your child/teen may slam the bedroom door as they refuse to tell you what is happening and why they are so upset. You may also hear from a teacher that your child/teen has been aggressive or said something hurtful to another student. Anger may cover hurt, humiliation, fear, and stress. It may also mask guilt, shame, grief, or envy. Or, it could be the tip of an iceberg of a submerged mass of frustration. As a parent or someone in a parenting role, you play an essential role in helping your child/teen connect to a greater understanding of their experience as they learn to identify their feelings and needs better.

Why Anger?

Whether your eleven-year-old breaks down in frustration over trying to complete math homework or your thirteen-year-old yells after not being allowed to attend an unsupervised party, anger, and its many accompanying feelings can become regular challenges if you don’t help your child/teen create plans and strategies for coping with and making space for these big emotions.

Today, in the short term, learning to manage anger can create

- a sense of confidence in your child/teen that they can regain calm and focus

- trust in each other that you and your child/teen have the competence to make space for a range of feelings in healthy ways and

- added daily peace of mind

Tomorrow, in the long term, your child/teen

- builds skills in self-awareness

- builds skills in self-control and managing feelings and

- builds assertive communication to communicate needs and boundaries critical for keeping them healthy and safe

Five Steps for Managing Anger

This five-step process helps you and your child/teen manage anger and builds essential skills in your child/teen. The same process can also address other parenting issues (learn more about the process).

Tip: These steps are best done when you and your child/teen are not angry, tired, or in a rush.

Step 1 Get Your Child/Teen Thinking by Getting Their Input

You can get your child/teen thinking about ways to make constructive choices about their behaviors when angry by asking them open-ended questions when your child/teen is calm. You’ll help prompt your child’s/teen’s thinking. You and your child/teen will also better understand their thoughts, feelings, and challenges related to coping with their anger so that you can both address them. In gaining input, your child/teen

- has the opportunity to become more aware of how they are thinking and feeling and understand when the cause of their upset is anger-related

- can think through and problem-solve any challenges they may encounter ahead of time

- has a more significant stake in anything they’ve thought through and designed themselves, and with that sense of ownership comes a greater responsibility for implementing new strategies and

- will be working with you on making decisions (and understanding the reasons behind those decisions) about critical aspects of their life

Actions

- Be curious about your child’s/teen’s feelings. You might start by asking questions.

- “How do you know when you are angry?”

- “What are some common things that make you angry?”

- “How can you tell when someone is angry with you? And what happens to you when someone is angry with you?”

- Use your best listening skills! Remember, what makes a parent angry can differ significantly from what angers a child/teen. Listen closely to what concerns your child/teen most without projecting your thoughts, concerns, and feelings. You will know you are in your best listening state if you are genuinely curious about your child’s/teen’s point of view.

- Reflect or paraphrase back what you hear. For example, if your child/teen says, “I’m so mad at my friend; he picked all my friends but me for his team.” You could say, “So I hear that he picked all your friends but not you, and I imagine you felt left out.”

- If your child/teen gives you some evidence for your guesses, make guesses about other deeper feelings. Remember, these guesses are based on them, not you. You are naming something your child/teen is not saying. For example, you could say, “I imagine not feeling picked made you feel hurt as well. Is that right?”

- Help your child/teen make the mind-body connection. Ask your child/teen, “What clues did your body give you that you were angry?” You can also say, “What are you feeling in your body now as you talk about it?”

Trap: Be sure you talk about anger at a calm time when you are not stressed or upset!

Because intense feelings like anger and hurt occur as you go about your daily life, you may not consider their role and impact on your child/teen. Intense feelings can majorly influence the day and your relationship with your child/teen. Learning about what

developmental milestones a child/teen is working on can help you better understand what your child/teen is going through and what might be contributing to anger or frustration.

2

- Eleven-year-olds are trying to assert their independence by imagining themselves in adult roles. They may get angry if they feel that you are exerting control when they are attempting to push away from you. As they grow their social awareness – being able to better see from another person’s perspective – they also increase their worries about being liked, who’s “in” and who’s “out,” and excluding others to gain popularity. They may also get angry when excluded or embarrassed in front of peers.

- Twelve-year-olds are gaining confidence and leadership abilities and are eager to figure out more serious adult issues and where they stand. With their growing social awareness, disturbing news and social issues could preoccupy them more than ever. They also have a lot of energy, yet they need their sleep, so they may have less resilience and find themselves more run down by stress, particularly when they have stayed up late. They may easily be edgy, moody, or angry as they deal with that stress.

- Thirteen-year-olds can have worries related to their newly acquired body changes. They can be highly sensitive as they work to define their independent identity while still being dependent upon you. They will feel an ever-greater sense of peer pressure, and though they may be pushing you away, they also require your continued support and guidance, including your approval. These sensitivities can spur anger when they feel misunderstood and desire more freedom.

- Fourteen-year-olds may act invincible, and like they know it all. Despite this, they still look to adults to set boundaries, negotiate rules, and listen to their needs. They are gaining interest in others as romantic partners and will have crushes, broken hearts, and worries related to relationships. They could get angry if embarrassed or rejected in front of peers, particularly crushes. They may enjoy academic challenges until they feel overwhelmed or underprepared. This fear of failure can lead to anger.

Remember that teaching is different than just telling. Teaching builds basic skills, grows problem-solving abilities, and prepares your child/teen for success. Teaching also involves modeling and practicing the positive behaviors you want to see, promoting skills, and preventing problems. This is also an opportunity to establish meaningful, logical consequences for unmet expectations.

Actions

- Learn together! Anger and hurt are essential messages to pay attention to. They mean emotional, social, or physical needs are unmet, or necessary boundaries (our rules or values) are violated. It’s important to ask, “Why am I feeling this way? What needs to change to feel better?”

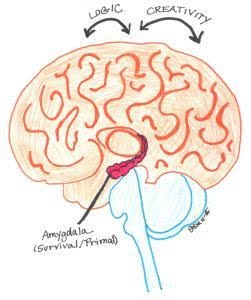

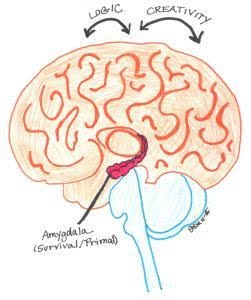

- Parents or those in a parenting role can benefit from understanding how stress is processed in the body and brain to ask helpful questions about your child/teen and learn about their

stress. Anytime you are emotionally shaken from stress, fear, anxiety, anger, or hurt, you are functioning from the part of your brain that developed first — the primal brain — or amygdala. The amygdala responds to stress by fighting, fleeing, or freezing and serves to help us survive dangerous situations. While we rarely face tigers and bears in the wild, several everyday interactions can activate your and your child’s/teen’s fight, flight or freeze response system. During these intense feelings, some chemicals wash over the rest of the brain, cutting off access to the part of our brain that allows for reasoning and problem-solving.

stress. Anytime you are emotionally shaken from stress, fear, anxiety, anger, or hurt, you are functioning from the part of your brain that developed first — the primal brain — or amygdala. The amygdala responds to stress by fighting, fleeing, or freezing and serves to help us survive dangerous situations. While we rarely face tigers and bears in the wild, several everyday interactions can activate your and your child’s/teen’s fight, flight or freeze response system. During these intense feelings, some chemicals wash over the rest of the brain, cutting off access to the part of our brain that allows for reasoning and problem-solving.

What does this mean as a parent or someone in a parenting role? You may notice that once your child/teen is upset, it is difficult to get through to them, or nothing may help the situation. Daniel Goleman, the author of Emotional Intelligence, refers to this as your child’s/teen’s brain being “hijacked.”2 When the brain is hijacked and in a stress response, your attempts at resolving the situation with problem-solving, reasoning, bribes, or threats will do little to solve the current conflict or change your child’s/teen’s behavior. Effective problem-solving requires logic, language, and creativity, though none can be well utilized when greatly upset. While in a stress response state, your child/teen cannot access the part of their brain, the prefrontal cortex, that engages in reasoning.

How can you help? When your child/teen becomes dysregulated, the first step is to help them return to a calm space before problem-solving or correction. Remember, helping your child/teen calm down does not mean that you are condoning misbehavior. Correction can take place after your child/teen has calmed down.

- As a parent, yelling will not dissipate anger. Research confirms that the expression of aggression, whether it’s yelling or hitting (including parents hitting, yelling, or spanking), exacerbates the anger.3 Furthermore, if they see those methods used, your child/teen will learn to model those behaviors, such as yelling and hitting. Expressing your anger physically will also erode your child’s/teen’s trust in you.

- Model behaviors and your child/teen will notice and learn.4 Here are some ways to deal with your own upset or anger.

- Create a plan for your self-regulation. This is critical so you’ll know exactly what you’ll say, where you’ll go to calm down, and what you’ll do and consider when calming down. Then, prepare your family so they understand your plan, will recognize it when they see it, and can learn from it.

- Recognize your anger. This self-awareness can come from several cues. Take note of physical symptoms — when they happen. It can cue you to calm down before choosing your next words or actions. Notice the signs, discuss what signs your child/teen notices, and take the following steps.

- Breathe first. Slowing down your breathing helps with calming down.

- Walk outside. The fresh air helps you breathe better, and the natural surroundings instantly calm.

- Distract yourself. Research has found that distraction can help calm rage. Reading a book or listening to music can help.

- Write. Writing down your angry thoughts (versus ruminating about them) can allow you to reevaluate your situation. You can reframe it, look at it from another perspective, or search for the silver lining. Reflecting in your writing on what you can learn from the situation has a calming effect.

- Brainstorm coping strategies. Depending on what feels right, you and your child/teen can use numerous coping strategies. But, when you are angry and upset, recalling what will make you feel better can be difficult. That’s why brainstorming a list, writing it down, and keeping it ready can be useful when your child/teen needs it. Here are some ideas from Janine Halloran:5 imagine your favorite place, take a walk, get a drink of water, take deep breaths, count to 50, draw, listen to music, and build something. Use this as a modeling opportunity and make a list of coping skills you will use for yourself the next time you feel angry or frustrated.

- Work on your family feelings vocabulary. Parents and those in a parenting role sometimes must become feelings detectives. If your child/teen shuts down and refuses to tell you what’s happening, you must dig for clues. Identifying your feelings is necessary to become more self-aware and understand your needs.

- Create a chill zone. During the time without pressures, design a “chill zone” or place where your child/teen decides they would like to go when upset to feel better. The only way this space serves as a tool for parents to promote their child’s/teen’s self-management skills is if they allow their child/teen to self-select the chill zone. You can and should practice using it and gently remind them of it when they are upset. “Would your chill zone help you feel better?” you might ask. But, if that space is ever used as a punishment or a directive – “Go to your chill zone!” – the control lies with the parents and no longer with your child/teen, and the opportunity for skill building is lost.

- Design a plan. When you’ve learned what happens in your brain and body when anger takes over, you know you need a plan ready, so you don’t have to think in that moment.

- Teach your child/teen how to stop rumination. If you catch your child/teen uttering the same upsetting story more than once, your child’s/teen’s mind has hopped onto the hamster wheel of rumination. In these times, it can be challenging to let go. Talk to your child/teen about the fact that reviewing the same concerns over and over will not help them resolve the issue, but talking about them, calming down, and learning more might help. Setting a positive goal for change will help. Discuss what they can do when thinking through the same upsetting thoughts.

- Reflect on your child’s/teen’s anger so you can be prepared to help. When reflecting on your child’s/teen’s feelings, you can think about unpacking a suitcase. Frequently, layers of feelings need to be examined and understood, not just one. Anger might just be the top layer. So, after discovering why your child/teen was angry, you might ask about other layers. Was there hurt or a sense of rejection involved? Perhaps your child/teen feels embarrassed? Fully unpacking the suitcase of feelings will help your child/teen feel better understood by you as they become more self-aware. Ask yourself:

- “What needs is my child/teen not getting met?” These needs can be emotional, like needing a friend to listen or give them attention, needing some alone time, or needing to escape a chaotic environment.

- “Can the issue be addressed by my child/teen alone, or do they need to communicate a need, ask for help, or set a boundary?” One of the hardest steps for many can be asking for help or drawing a critical boundary when needed. First, you’ll need to find out what those issues are in your reflections with your child/teen. But then, guiding them to communicate their needs is key.

- Help your child/teen repair harm when needed. A critical step in teaching your child/teen about managing anger is how to repair harm when they’ve become overcome by anger and hurt others. Mistakes are a critical aspect of their social learning. Everyone has moments when they hurt another. But, it’s that next step that they take that matters in repairing the relationship.

- Find small opportunities to help your child/teen mend relationships. Siblings offer a regular chance to practice this! If there’s fighting, talk to your child/teen about how they feel first. When you’ve identified that they had a role in causing harm, brainstorm together how they might make their sister feel better. You might ask, “What could you do?”

- Allow your child/teen to supply answers; you may be surprised at how many options they generate. Support and guide them in selecting one and doing it.

- Teach assertive communication through “I-messages.” When you or your child/teen are uncomfortable with disagreeing or arguing with another, it can be difficult to know how to respond in ways that won’t harm yourself or others. That’s why teaching and practicing I-messages can provide a structure for what you can say. This statement works effectively from partner to partner, parent to child/teen, and child/teen to child/teen. Here’s an example: “I feel _____________(insert feeling word) when you____________ (name the words or actions that upset you) because________________.”

- Here’s how it might sound if a parent is using it with a child/teen: “I feel frustrated and angry when you keep playing your video game and don’t seem like you are listening because I feel ignored, and I believe what I have to say is important for both of us.”

- If you are helping your child/teen use this in communicating with a friend who has angered them, here’s how it might be used: “I feel angry when you pick all of our friends for your team but me because I was counting on playing with everyone, and now I am on a team with others I don’t know.” Practice the wording together with your child’s/teen’s specific issue.

- Create a family gratitude ritual. People are inundated with daily negative messages through the news media, performance reviews at school or work, and challenges with family and friends. It’s easy and often feels more acceptable to complain than to appreciate. Balance out your daily ratio of negative to positive messages by looking for the good in your life and stating it. Model it and involve your child/teen. This is the best antidote to a sense of entitlement or taking your good life for granted while wanting more and more stuff. Psychologists have researched gratefulness and found that it increases people’s health, sense of well-being, and ability to get more and better sleep at night.6

Trap: If you tell or even command your child/teen to make an apology, how will they ever learn to do so while feeling genuine? Apologizing or making things right should never be assigned as a punishment since the control lies with the adult. It robs the child/teen of the opportunity to learn the skill and internalize the value of repairing harm. Instead, ask your child/teen how they feel they should make up for the hurt they’ve caused and help them implement their idea.

Step 3 Practice to Grow Skills and Develop Habits

Practice can take the form of cooperatively completing the task together or trying out a skill with you as a coach and ready support. Practice is not only nice; children/teens must internalize new skills. Practice makes vital new brain connections that strengthen each time your child/teen performs the new action.

Actions

- Use “I’d love to see…” statements. When a child/teen learns a new ability, they are eager to show it off! Give them that chance. Say, “I’d love to see how you use your chill zone to help you.” This can be used when you observe their upset mounting.

- Recognize effort. You could say, “I notice how you took deep breaths when frustrated. That’s excellent!”

- Accept feelings. If you want to help your child/teen become emotionally intelligent in managing their biggest feelings, it is important to acknowledge and accept them—even ones you don’t like! When your child/teen is upset, consider your response. You could say, “I hear you’re upset. What can you do to support yourself at this moment? ”

- Practice deep breathing. Because deep breathing is a simple practice that can assist your child/teen anytime, anywhere, it’s important to get plenty of practice to make it easy to use when needed. Here are some enjoyable ways to practice together!4

- Hot Chocolate Breathing. Pretend to hold your hot cup of hot chocolate in both hands in front of you. Breathe in deeply the aroma of the chocolate. Then, blow it out to cool it in preparation for drinking. Do this to the count of five to give your child/teen practice. Then, look for chances to practice it regularly.

- Ocean Breathing. Practice making the noise of the sea waves while breathing deeply from your diaphragm. Close your eyes with your child/teen and imagine your anger is a fiery flame waiting on a sandy shore. And as you breathe life into the ocean waves, they grow closer and closer to the flame to extinguish it.

- Follow through on repairing harm. When your child/teen has caused harm, it’s easier to shrink away in shame and attempt to escape the problem, hoping time will heal all wounds. But, if real damage has been done – emotionally or physically – then your child/teen needs to take some steps to help heal that wound. It takes tremendous courage, however, to do so. So, for your child/teen to learn that the next choice can be their best choice and that they can make up for the harm they’ve caused, they need your guidance, encouragement, and support in following through on those steps. They are learning the invaluable skill of responsible decision-making.

- Include reflection on the day in your bedtime routine. Give children/teens the chance to reflect on what’s good and abundant in their lives. You might ask, “What are your highs and lows of the day?” Sharing highs and lows allows your child/teen to share difficult moments and reflect on their day’s bright spots. Grateful thoughts can be a central contributor to happiness and well-being.

Step 4 Support Your Child’s/Teen’s Development and Success

At this point, you’ve taught your child/teen some new strategies for managing anger so that they understand how to take action. You’ve practiced together. Now, you can offer support when it’s needed by reteaching, monitoring, coaching, and, when appropriate, applying logical consequences. Parents naturally provide support as they see their child/teen fumble with a situation where they need help. This is no different.

Actions

- Ask key questions to prompt thinking. You could ask: “You are going to see Julie today. Do you remember what you can do to assert your feelings?”

- Learn about your child’s/teen’s development. Each new age presents different challenges. Being informed about your child’s/teen’s developmental milestones will offer you empathy and patience.

- Reflect on outcomes. You could say, “Seems like you couldn’t get to sleep last night because you were feeling angry about our argument. How did it impact your day at school? What could we do tonight to help?”

- Stay engaged. Working together on ideas for trying out new and different coping strategies can help offer additional support and motivation for your child/teen when tough issues arise.

- Engage in further practice. Create more opportunities to practice when all is calm, and you are engaged with each other.

- Apply logical consequences when needed. Logical consequences should come soon after the negative behavior and need to be provided in a way that maintains a healthy relationship. Rather than punishment, a consequence is about supporting the learning process. First, get your own feelings in check. Not only is this good modeling, but when your feelings are in check, you can provide logical consequences that fit the behavior. Second, invite your child/teen to discuss the expectations established in Step 2. Third, if you feel your child/teen is not holding up their end of the bargain (and it is not a matter of them not knowing how), apply a logical consequence as a teachable moment.

- If there are strong feelings in your household most days, most of the time, then it may be time to consider outside intervention. Physical patterns may begin to set in (feelings of depression) that require the help of a trained professional. Seeking psychological help is the same as going to your doctor for a physical ailment. The following are some resources to check out.

- American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) has definitions, answers to frequently asked questions, resources, expert videos, and an online search tool to find a local psychiatrist. http://www.aacap.org

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Healthy Children provides information for parents about emotional wellness, including helping children handle stress, psychiatric medications, grief, and more. http://www.healthychildren.org

- American Psychological Association (APA) offers information on managing stress, communicating with kids, making stepfamilies work, controlling anger, finding a psychologist, and more. http://www.apa.org

- Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies (ABCT) provides free online information so that children and adolescents can benefit from the most up-to-date information about mental health treatment and learn about important differences in mental health supports. Parents can search online for local psychologists and psychiatrists for free. http://www.abct.org

No matter how old your child/teen is, your positive reinforcement and encouragement have a significant impact.

If your child/teen is working to grow their skills – even in small ways – it will be worthwhile to recognize it. Your recognition can go a long way in promoting positive behaviors and expanding your child’s/teen’s confidence. Your recognition also promotes safe, secure, and nurturing relationships — a foundation for strong communication and a healthy relationship with you as they grow.

There are many ways to reinforce your child’s/teen’s efforts. It is essential to distinguish between three types of reinforcement: recognition, rewards, and bribes. These three distinct parenting behaviors have different impacts on your child’s/teen’s behavior.

Recognition occurs after you observe the desired behavior in your child/teen. Noticing and naming the specific behavior you want to reinforce is key to promoting more of it. For example, “You stopped and took the time to breathe when you were starting to get angry — I love seeing that!” Recognition can include nonverbal acknowledgment such as a smile, high five, or hug.

Rewards can be helpful in certain situations by providing a concrete, timely, and positive incentive for doing a good job. A reward is determined ahead of time so that the child/teen knows what to expect. It stops any negotiations in the heat of the moment. A reward could be used to teach positive behavior or break a bad habit. The goal should be to help your child/teen progress to a time when the reward will no longer be needed. If used too often, rewards can decrease a child’s/teen’s internal motivation.

Unlike a reward, bribes aren’t planned ahead of time and generally happen when a parent is in the middle of a crisis (To avoid disaster, a parent offers to buy ice cream if the child/teen leaves the party). While bribes can be helpful in the short term to manage stressful situations, they will not grow lasting motivation or behavior change and should be avoided.

Trap: It can be easy to resort to bribes when recognition and occasional rewards are underutilized. If parents or those in a parenting role frequently resort to bribes, it is likely time to revisit

the five-step process.

Actions

- Recognize and call out when it is going well. It may seem obvious, but it’s easy not to notice when all is moving along smoothly. Noticing and naming the behavior provides the necessary reinforcement that you see and value your child’s/teen’s choice. For example, when children/teens complete their homework on time, a short, specific call out is all that’s needed: “I notice you completed your homework today on your own in the time we agreed upon. Excellent.”

- Recognize small steps along the way. Don’t wait for the big accomplishments – like the full bedtime routine to go smoothly – to recognize effort. Remember that your recognition can work as a tool to promote more positive behaviors. Find small ways your child/teen is making an effort and let them know you see them.

- Build celebrations into your routine. For example, after getting through your bedtime routine, snuggle and read before bed. Or, in the morning, once ready for school, take a few minutes to listen to music together.

Closing

Engaging in these five steps is an investment that will strengthen your skills as an effective parent on many other issues and develop essential skills that will last a lifetime for your child/teen. Through this tool, children/teens have opportunities to become more self-aware, deepen their social awareness, exercise their self-management skills, work on their relationship skills, and demonstrate and practice responsible decision-making.

stress. Anytime you are emotionally shaken from stress, fear, anxiety, anger, or hurt, you are functioning from the part of your brain that developed first — the primal brain — or amygdala. The amygdala responds to stress by fighting, fleeing, or freezing and serves to help us survive dangerous situations. While we rarely face tigers and bears in the wild, several everyday interactions can activate your and your child’s/teen’s fight, flight or freeze response system. During these intense feelings, some chemicals wash over the rest of the brain, cutting off access to the part of our brain that allows for reasoning and problem-solving.

stress. Anytime you are emotionally shaken from stress, fear, anxiety, anger, or hurt, you are functioning from the part of your brain that developed first — the primal brain — or amygdala. The amygdala responds to stress by fighting, fleeing, or freezing and serves to help us survive dangerous situations. While we rarely face tigers and bears in the wild, several everyday interactions can activate your and your child’s/teen’s fight, flight or freeze response system. During these intense feelings, some chemicals wash over the rest of the brain, cutting off access to the part of our brain that allows for reasoning and problem-solving.